Urban green spaces are an important tool for growing cities to ensure the wellness of their citizens and to help fight climate change.

While there are many benefits to big-city life, such as better job opportunities and access to a wider and more diverse community, there are also many challenges. High rent prices, lengthy commutes, pollution, noise, and traffic can all take a toll on our health and happiness and negatively impact the quality of life of citizens.

Much research has been conducted over the years that show how important green spaces are for both the physical and mental wellbeing of residents. According to a recent study by the International Journal of Environmental Health Research, spending as little as 20 minutes in a park can significantly boost how satisfied we feel about our lives.

And to ensure that cities can offer a reasonable quality of life in the not-so-distant future, the creation and preservation of green spaces has become a growing focus. The world’s urban centers already support 55 percent of the world’s population, but The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs predicts this number will reach 68 percent by the year 2050.

The benefits of urban green spaces aren’t just limited to city residents. As climate change reaches a crisis point, cultivating natural environments within urban landscapes is an excellent way of reducing the carbon footprint of a city.

Green spaces can also help to safeguard citizens against the immediate dangers of climate change. Dense vegetation creates shady areas that help to cool cities during heat waves, and areas of soil and grass can help mitigate prolonged flooding by soaking up excess water.

In addition, green spaces can be a huge boon for tourism. New York City’s Central Park is second only to the Statue of Liberty when it comes to sightseeing in the Big Apple and a quick scroll through the Instagram feed of any recent visitor to Singapore is sure to reveal a picture of the city’s famed botanical “supertrees”.

Green spaces can be what makes or breaks a city, and whether it’s for the benefit of citizens, the environment, or tourism, governments are devising some clever ways to incorporate nature into urban environments for future generations.

Reclaiming a lost landscape

In the South Korean capital of Seoul, the government has carefully worked to restore the city’s lost Cheonggyecheon Stream, which was paved over and converted into a freeway in the 1950s.

The Cheonggyecheon Stream restoration project was initiated in 2003 by the then-Seoul mayor Lee Myung-Bak. At the time, the central city lacked aesthetic appeal and he believed the regeneration of this historic green space would help to boost Korea’s image and encourage foreign investment and tourism. He also believed the stream would also provide a flood relief channel for the central city and provide a more appealing environment for workers and residents.

The project was considered controversial as it meant demolishing the existing freeway, making it tougher to bring cars into the central part of the city. To alleviate fears of traffic congestion, dedicated bus lanes and a rapid bus service were introduced, with the bonus of reducing city emissions.

Opened in 2005, the modern Cheonggyecheon Stream follows the path of the original river, providing a pedestrian-only green space for office workers to quietly sip coffee, elderly people to relax, and children to play.

According to a case study by sustainable design non-profit organization The Landscape Architecture Foundation, the restored stream and riverbed is helping to cool the city’s urban air temperatures, has reduced small-particle air pollution by 35 percent, and attracts 1,408 international tourists each day to the benefit of surrounding businesses.

Creating an urban jungle

Walking through Singapore’s CBD, it seems every inch of the city that isn’t actively in use for infrastructure is dominated by lush greenery. The city’s skyscrapers create a tropical canopy, with eye-catching vertical gardens, rooftop farms, sky terraces, and dedicated botanical floors.

But this is no accident. When Singapore gained independence from Malaysia in 1965, founding president Lee Kwan Yew envisioned a vibrant garden city, with ample green space and urban jungle to be enjoyed by citizens.

Singapore’s urban planning has been eternally influenced by Yew’s original vision, but with five million residents packed into just 269 square miles (697 square kilometers), keeping the city sufficiently green is no easy feat. The lack of space has inspired Singapore to look to the skies, to retain its status as a garden city through population growth and urbanization.

In 2009, the government launched the LUSH program, which required green spaces to be incorporated into all new developments. The program allows companies to utilize walls, terraces, and rooftops to fulfill their quota, inspiring some innovative solutions. The stunning Parkroyal on Pickering Hotel is often cited as the program’s biggest success, with its curvaceous sky gardens and tropical terraces.

The LUSH project was further intensified in 2017 after successfully adding 40 hectares of urban greenery of the city. Green spaces are a key part of Singapore’s long-term strategy for low emissions and the diversification of the city’s wildlife. A recent observation by the Singapore National Parks Board recorded 53 bird and 57 butterfly species across 30 different rooftop gardens.

The government has set the ambitious target of doubling the cites high-rise greenery by 2030, for which the LUSH program is key. As of June this year, the nation’s green space obsession even saw rooftop gardens installed on city buses.

Greenifying abandoned spaces

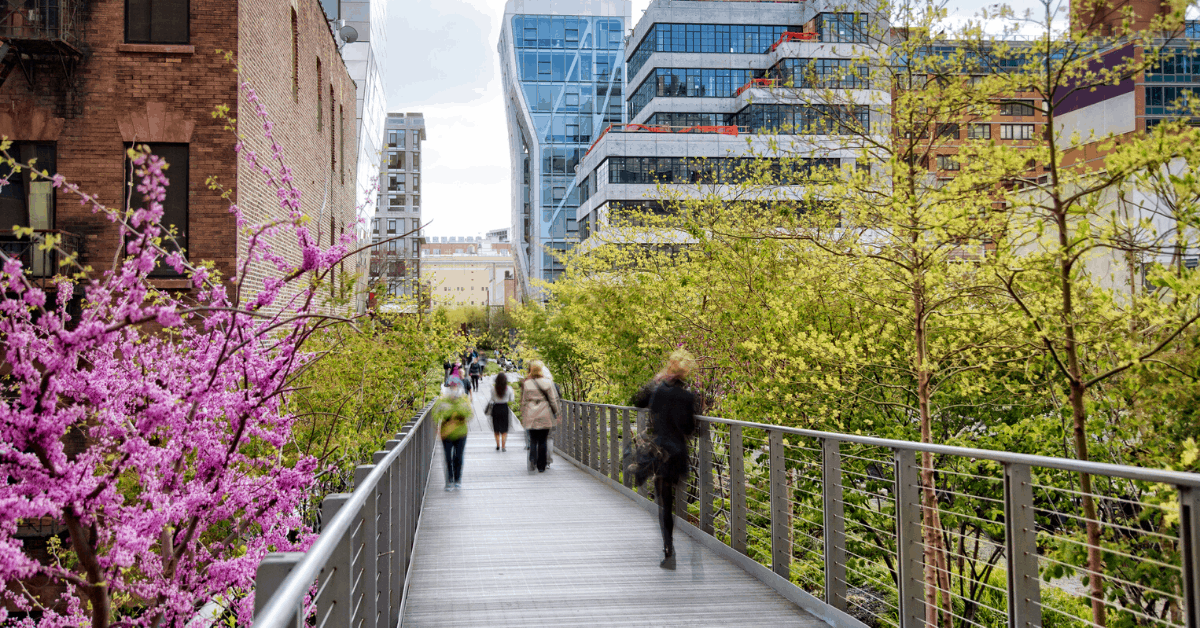

In July of this year, the City of New York opened the final section of an ambitious urban renewal project, known as the High Line.

Located in west Manhattan, the High Line is a 1.45-mile public park, built upon a once-derelict New York rail line. Originally used to transport freight to factories and warehouses, the rail line was decommissioned and abandoned in 1980 after the island’s manufacturing industry ground to a halt.

The railway became an urban ruin and a serious eyesore, earmarked for eventual demolition. However, in 1999, two local community members formed an organization called Friends of the High Line and successfully petitioned the local government to repurpose the elevated urban space for use by city residents.

Designed by architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the now-completed High Line is a poster child for successful urban development, widely praised in both the U.S. and abroad for its innovative design. The space preserves the rail line’s original features, including tracks, steel beams, and girders, which are used to frame and define a variety of green spaces, from wild grey birch forests and grasslands to manicured parks and gardens.

The park has revitalized a once dull and industrial part of New York City, by providing green recreation spaces that are elevated up and away from the stress of the city. The value of real estate surrounding the High Line has sharply increased, showing the high value placed on green space proximity by residents and businesses alike.

But the positive effects of the High Line aren’t limited to west Manhattan. The park uses a green roof system that traps water, reducing stress on the city’s sewer network during periods of high rainfall, and has become a valuable tourist attraction. The High Line is considered one of the must-see attractions in New York City and is featured in most NYC travel guides.

The future of urban green spaces

What might have once been a simple corner park, urban green spaces today are considerably more creative. Green space fever is spreading, and governments are formulating bold new strategies to ensure city landscapes remain green and beautiful, alongside population growth and urbanization.

In 2018, the City of London set the exciting target of becoming the world’s greenest city, which included the building of a 23-kilometer nature reserve and cycle path and the transformation of large underutilized spaces to create new biodiverse natural habitats. If their plan is a success, then by the year 2050 an incredible 50 percent of London city will be dedicated to green space, rivers, and lakes.

The French Canadian capital of Montreal has always led the way when it comes to green energy and sustainable infrastructure but the local government has taken things up a notch, unveiling plans for a colossal new 3,000-hectare city-adjacent wilderness area.

With climate change directly threatening the livability of the world as a whole, these green space initiatives are one part of the work that needs to be done to safeguard future generations.

5 minutes can change the world

This Earth Day, we’re joining Time for Climate Action! There are so many ways to do good for the planet that are quick and easy, but have a lasting long-term impact. Take action today!